RAMALLAH, 6 DECEMBER—I met Saed in Aida refugee camp in the first week in November when he gave me a tour of the crowded community in which he grew up. A young man still in his twenties, Saed works at one of several cultural centers located in Aida camp. He holds a degree in psychology from the University of Bethlehem, where he is a part-time lecturer in Arabic.

Aida is the smallest of the refugee camps in the West Bank. It is densely populated, and its narrow streets are crowded with buildings huddled together like people seeking shelter from a storm. Surrounded on two sides by the apartheid wall, Aida is also the most frequently raided camp.

Down a narrow street near the entrance to the camp a large blue gate is set into the concrete wall. It is from this gate the I.O.F. launches its raids into the camp. Farther along the same street, a watch tower and gun turret stand guard over the camp. From there, snipers frequently shoot into the streets and apartment buildings bellow.

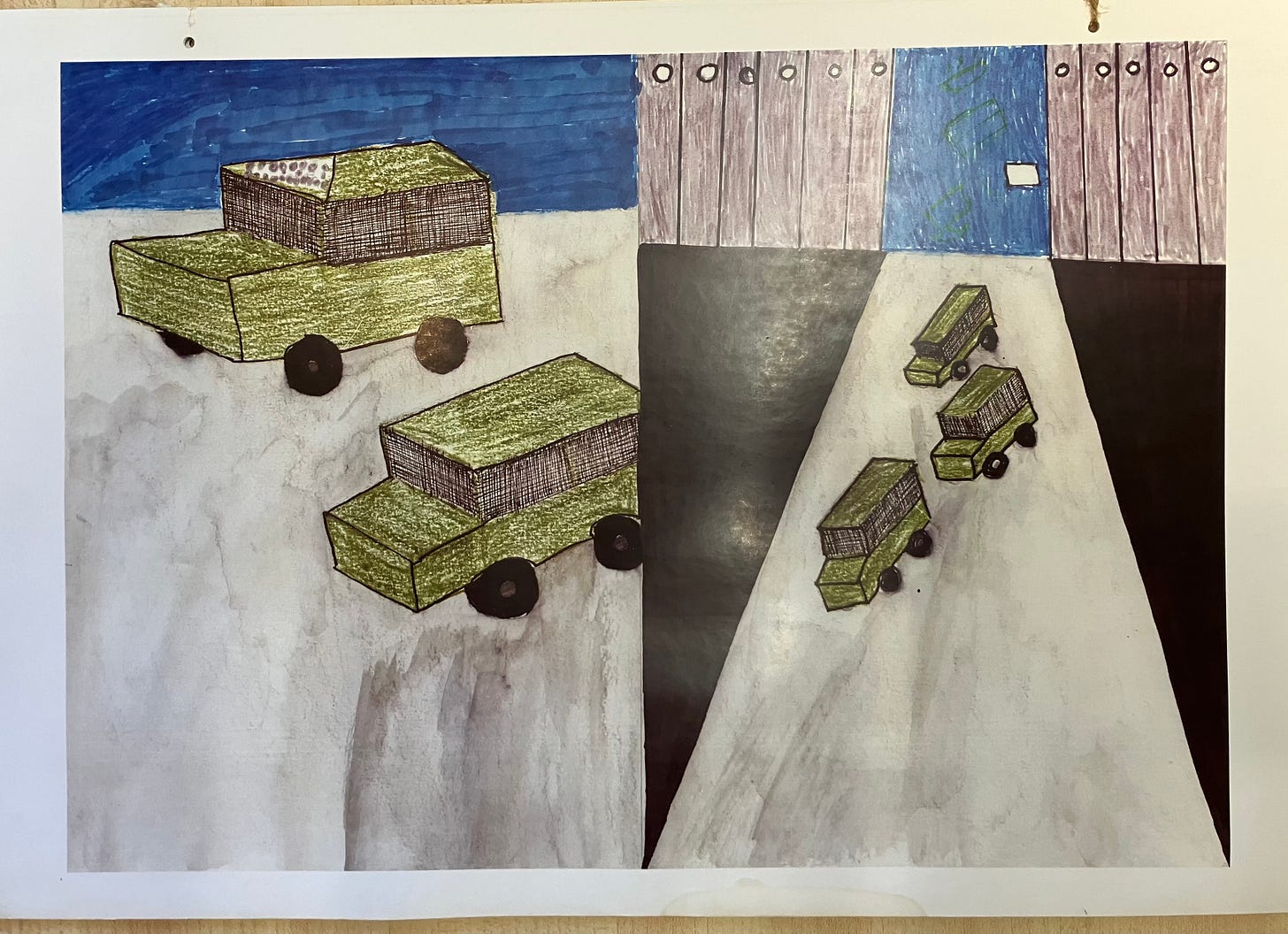

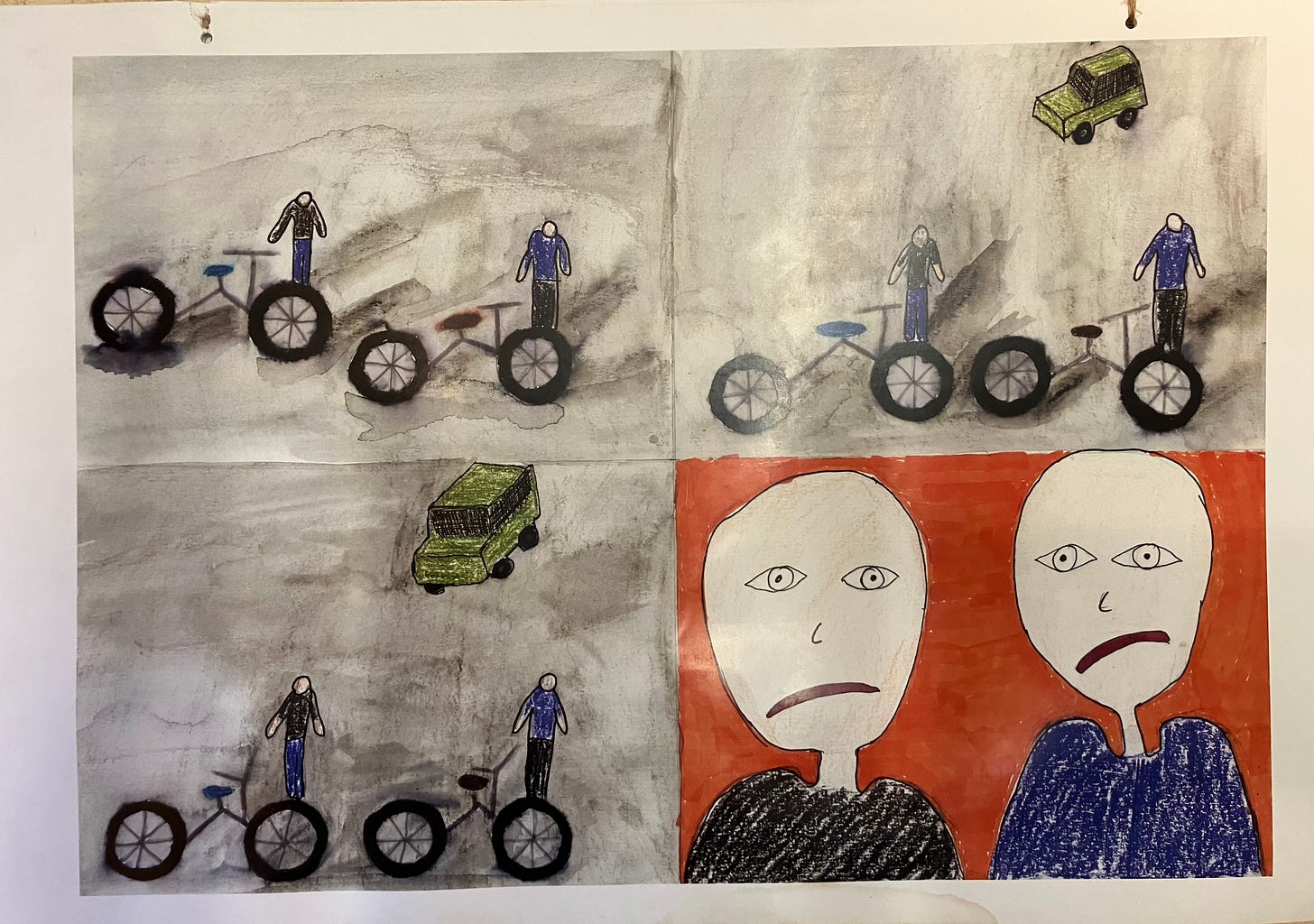

After the tour, I spent another hour in Saed’soffice. Among the many things we discussed was the art therapy program the center runs for children. As we talked he pulled out a stack of drawings that the children had done—all of them prior to 7 October of last year.

Each child had drawn and colored a series of large storyboards depicting a difficult experience and showing how it was eventually resolved with the help of others—a teacher, a therapist, family, friends. The storyboards were bound into simple books with twine.

Saed pulled out three or four of these from the stack and talked me through the drawings. They were remarkable for their emotional impact. Many of them were equally remarkable for their artistry. These drawings were fresh and powerful, objects of art worthy of a gallery display. So I thought at the time and still do.

This afternoon, wrapping up my work on this sojourn in the West Bank, I texted Saed. “Hi. How are you?”

His response arrived two hours later. “Hi. Alhamdulillah, I’m doing good.”

I smiled when I read his reply. I know the word alhamdulillah well and have written about it previously. Frequently used among Muslims and Christians in the West Bank, it is an Arabic phrase giving thanks to God for all that is good—and all that is difficult—in a person’s life. Any good news in the West Bank is always to be celebrated.

And then his next message arrived—with a photograph. My heart fell when I saw the military uniforms. “The I.O.F. invaded the center,” he texted. “They stole the art of the kids that I showed you.

During my first visit to the West Bank this kind of news would leave me in tears. Now I’m nearly cried out. Many perfectly lovely days in the West Bank go suddenly and terribly sideways because the soldiers and settlers who illegally occupy this land are sociopathic. They delight in terrorizing Palestinians. They delight in sadism.

Now, in my final week in Palestine, at least for the time being, the grief and anger pass more quickly and I’m actually starting to laugh. It’s a dark humor to be sure. Stealing children’s art?! Really?!! If you will pardon my language: How fucked up do you have to be to steal children’s art?

Think about it: They are dressed for combat, armed to the teeth, and stealing children’s art. There’s something darkly humorous about that. Perhaps because it’s so irrational.

But this irrationality is rooted in fear and is also deadly. They are indeed afraid of children’s art. Because they are afraid of children. They’re afraid of what these children represent: The future of Palestine. This is why they shoot boys who throw rocks in the West Bank. And why they are killing so many children in Gaza.

Previously published on West Bank Alerts, The Floutist’s associated publication.

There are no words . . .

I visited the Dachau Memorial Concentration Camp many many years ago. At that time one of the final exhibition rooms was showing paintings and drawings by children imprisoned in the Camp. They were difficult pictures to process and clearly represented the way in which the children's imagination had been shaped by the sentence inflicted on them. When I saw the two paintings depicted in Cara Marianna's article, the memories of Dachau came flooding back.