8 SEPTEMBER—Many commentators have attempted to describe the astonishing devolution of Democratic Party politics into sheer marketing: Kamala Harris as product, “new and improved” like a laundry detergent or a frozen dinner. Vanessa Beeley comes up with “cartoon theatrics,” and it is as good as I have seen. In two words the British journalist captures from a useful distance the infantilism of the Harris-for-president campaign along with the Hollywoodization of American political culture.

I thought I had seen everything in this line until a few days ago, but in this, the most unserious political season of my lifetime, it is incautious to make any such assumption. There is always more, something worse, another step down into a sort of political nihilism that leaves the electorate stupefied as the imperium conducts its violent, illegal business.

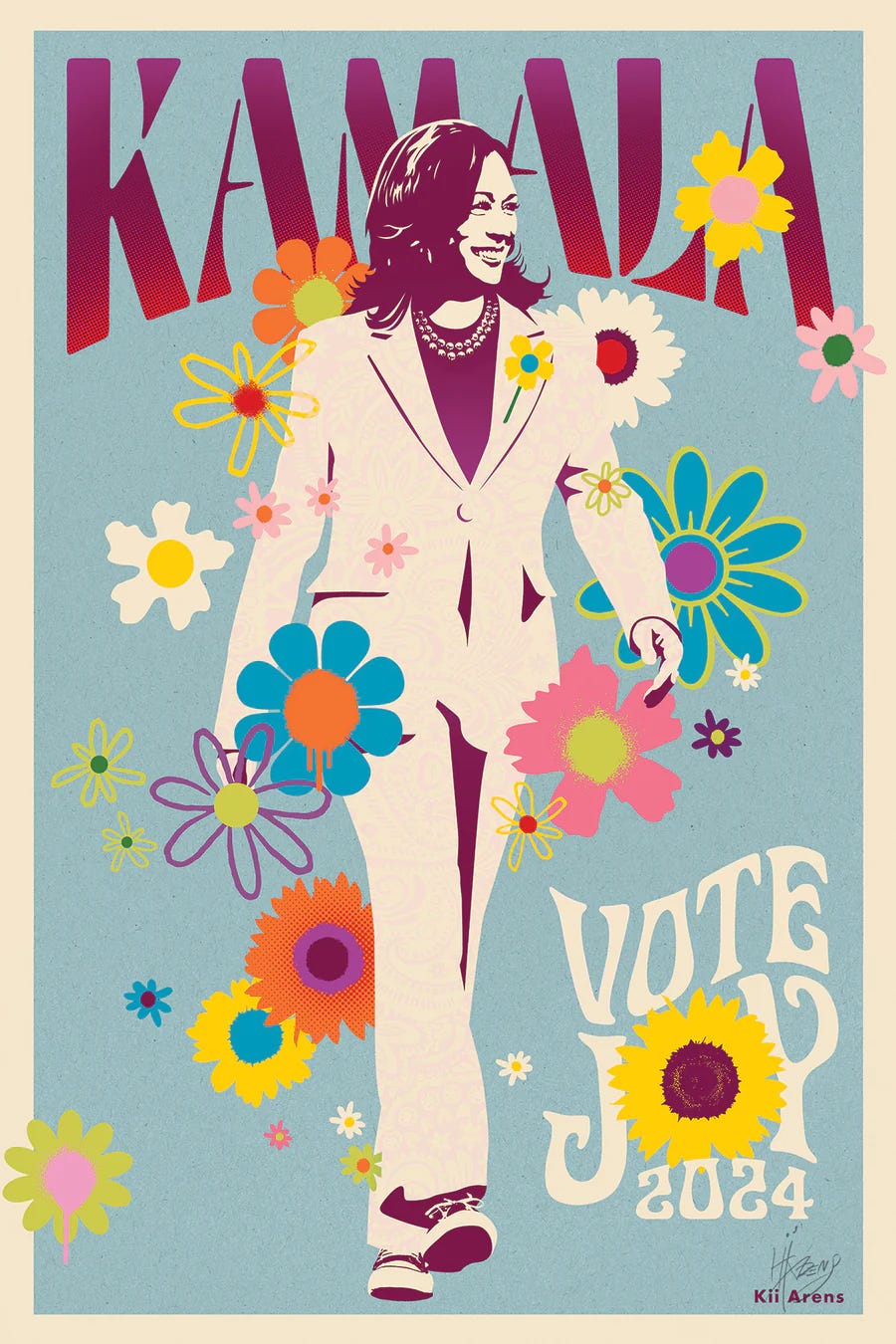

A truly vulgar graphic artist named Kii Arens now gives us a Kamala Harris campaign poster that is a beyond-belief case in point. This is “Kamala” against a pastel field, no surname necessary, the presidential candidate as a striding figure out of the 1960s counterculture, an heroic hippie. I hope you are ready for the tag line. It is “Vote Joy 2024.”

My mind was on other things when I first came across this poster. And it landed abruptly as an assault and an insult all at once. Just glance at it for now: This is how some Democratic voters, and I suspect many, want to imagine a candidate who supports and advances, among various other late-imperial crimes, a genocide of world-historical significance. The imagery seems, somehow, an almost criminal violation of human intelligence.

Kii Arens makes his living doing pop-art graphics—logos and such—for a lot of show business people and credits Saturday morning children’s television as his primary inspiration. Out in California he owns and runs the La La Land Gallery, which seems about right.

Kii Arens seems to take himself very seriously indeed. And it goes this way: Either Kii Arens has overestimated the gullibility, self-delusions, and unconsciousness of liberal voters, especially those who consider themselves “progressive” or “left,” or I have underestimated the same.

I fear Kii Arens may have me on this one. “People are really excited about this poster,” he said in a brief video interview after giving away copies of it at the Democrats’ convention in Chicago. “People are connecting emotionally to my art.”

■

When I first saw the “Kamala” poster it was via a social media message Katrina vanden Heuvel sent out, with cheerful approval, on “X.” Ms. vanden Heuvel, as many readers will know, is the editorial director of The Nation. It is important to take note. In “Vote Joy 2024” we find the denouement of the long, pitiful story of what has become of the American “left” in the course of some decades and why this term now requires quotation marks.

I have long thought politics can be usefully read as an expression of antecedent cultural and psychological occurrences. This is how I view the Kii Arens poster and why I think it merits careful scrutiny: It is a window, or maybe a Rosetta Stone, in which we can read the coded interiority of the “left’s” psychic journey from the honorable commitments of earlier times to… to what?... to a state of willful political and intellectual immaturity.

Now study the poster for a good few minutes.

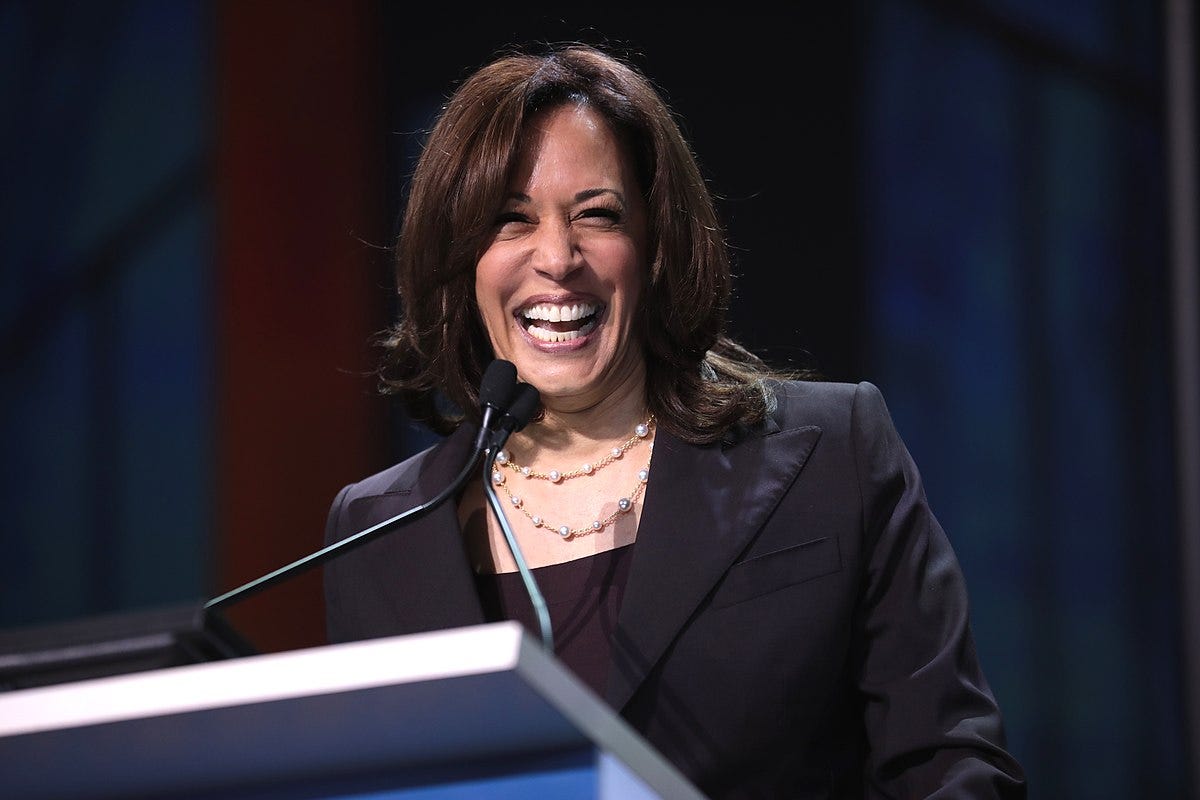

There is Harris, of course, in her standard pantsuit and pearls. So: the political candidate with whom we are familiar. She is serious and altogether credible, but wears that having-fun, sorority-sister smile that endears her to many Democratic voters.

There are the flowers splashed across the whole of the graphic. These are essential to the overall effect. They are the kind of flowers you see on the walls of grade-school art classes. And they are “flower power” flowers. They bathe Harris in an aesthetic of innocence, with a subliminal suggestion of a childlike blamelessness. Note Harris’s stride in this connection: It is purposeful, but with the air of a guilt-free girl walking in a garden.

And then the typefaces. The “Vote Joy 2024” in the lower right immediately draws the eye. It is subtly but unmistakably a reference to the posters associated with the late–’60s rock scene—a variation on Psychedelic Fillmore West and Psychedelic Fillmore East (which, believe it or not, are two recognized typefaces).

Kii Arens has added a couple of small touches I must mention for the sheer fun of them. He has inscribed a faint paisley pattern into Harris’s presidential pantsuit. Paisley. Dwell upon paisley for a sec and see what you think this means. You may have to be of a certain age to understand what Arens intends to say when he dresses Harris in a paisley suit, but voters of a certain age are among those the Democrats must deceive, and so betray, if “Kamala” is to go the distance.

And beneath the pantsuit he has Kamala Harris wearing canvas sneakers—those flimsy black Converse things favored by young people who are, to put it charitably, casually dressed. So: an appeal to another constituency that must fail to notice that behind “Kamala” there is no actual person named Kamala Harris.

Sheer fun: and if you think about it, a very pure case of pointedly manipulated imagery.

If I were a certain kind of columnist, I would say the poster Kii Arens has made to express his enthusiasm for the Harris campaign (which he now sells for $47, extra for framing) is, as was just shouted to me from across the room, “a complete mind-fuck.” But I am not that kind of columnist. I will not say this poster, with all its flower power iconography in behalf of a warmonger, is a complete mind-fuck.

I would say the physiologically ambitious intent of this poster is to perform the act of love on the cerebral cavity. Way more acceptable for a family publication such as Consortium News.

I do not know whether the Harris campaign commissioned this thing. I suspect they like it well enough but did not order it up. In the video interview mentioned above, Kii Arens comes over as an averagely guileless, averagely indoctrinated, averagely numbed liberal with no clue of the diabolic cynicism with which the Democratic Party is inventing Kamala Harris of whole cloth.

My read: “Vote Joy 2024” comes straight out of Kii Arens’s unconscious, and this is what makes it interesting. It is fair enough, and useful, if we think of Arens as the id of those “progressive” and “left”–inclined voters the Harris campaign must seduce if “Kamala” is to win in November.

It is not clear how many Democratic voters buy into the various signifiers Arens has inscribed into his poster. I suspect he speaks for very many—someone should check his sales—but let us set this aside. His work is certainly a disturbing measure of the extent to which those who could well propel Harris to the White House in November are prepared to delude themselves into seeing things in Kamala Harris that are simply not there.

“My art is supposed to reflect positivity, hope, and joy,” Arens says in the videoed interview. There are a lot of Democrats looking for just these things in the figure of Kamala Harris. But this is not the remark of an aware or self-aware American in the late-summer of 2024. It is the remark of someone who is determinedly neither.

■

Kii Arens has slathered on the semiology in his “Vote Joy 2024” poster with a trowel. Semiology is the science of signs, of significations. In what signs is Kii Arens trafficking?

As an aesthetic object the Arens poster is crude, but this is of no matter. It is dense with many-layered signifiers, and these are what matter. There are important insights to be gained as we examine these layers and discover what, taken together, they have to say—about the long regression at the left-hand end of America’s politics, about liberal and “left” voters’ fears, fantasies, and failures of nerve.

Here is the Brittanica definition of “flower power.” It is a good place to begin.

Flower power: the belief that war is wrong and that people should love each other and lead peaceful lives—used especially to refer to the beliefs and culture of young people (called hippies) in the 1960s and 1970s.

Instantly we learn something.

We have heard daily talk of “joy” and “vibes” since the Democratic Party’s elites and donors undemocratically imposed Kamala Harris as their 2024 candidate. And now we find, via an admittedly goofy but probably representative Harris voter with an amateur gift for social psychology, that beneath all this compulsive “positivity” there seems to lie a strong streak of nostalgia.

Why, the obvious question, do the liberal voters for whom Arens speaks, or to whom he speaks, or both, indulge in a nostalgia for a time a lot of them, maybe most, never knew? Why is it important that they identify so strongly with those whose political and cultural commitments, however gauzily recalled, gave the 1960s the reputation the decade has in the public consciousness.

Why the historical reference? Answer this and we can see into the strange dynamic driving the wave of enthusiasm for the Harris campaign as it floats along on puffy clouds of joy and good vibes.

Nostalgia, I have long argued, is at bottom a symptom of depression. Nostalgists are those who retreat into the past as a refuge from a present they find in one or another way unbearable. And here I offer a corollary thought: The sensation of powerlessness is a primary cause of depression. Any good psychiatrist would confirm this.

With this in mind, think about all those people “connecting emotionally” to Kii Arens’s iconography, and then all the others who may not have not seen it but would similarly identify with it. That these people are in some inchoate way nostalgic is beyond argument. The follow-on conclusion seems to me equally evident: All the talk of joy and vibes is at bottom a mask for a more or less prevalent depression people cannot admit to themselves they suffer.

As the Brittanica notes in it stuffy, wooden fashion, “peace” and “love” were among the totemic terms that characterized the 1960s counterculture Arens unsubtly references. But you cannot, plain and simple, walk around today talking of either and expect to be taken seriously. Ours is not a polity that gives any credence to notions of peace and neighborly love. This is absolutely out. Propagandists and ideologues have long since transformed mainstream American culture—since the Reagan years, I would say—into a culture of war and animus.

In this connection, we should consider just briefly the voters to whom the Kii Arens poster appeals. While losing themselves in the semiology of flowers, to take one example, they are all for the vicious proxy war in Ukraine Kamala Harris supports and the broader provocation of the Russian Federation that is the Biden regime’s intent. This is what has become of the previously antiwar left: What was once down is now up, and vice-versa. Think about this kind of thing long enough and, I warn you, you will get something that approximates nitrogen sickness.

And so we return to joy and vibes. These are excellent terms for those given to fantastic readings of Kamala Harris. To stand for peace and love 50 or 60 years ago was to challenge what people used to call “the establishment.” They had meanings, these terms, however angelic were those professing them. “Joy” and “vibes” have no meanings, which is their very point. This is why they have caught on like fires in a dry forest. They do not signify challenges to anything; they license an extraordinary flinch from everything.

Everything: America’s full support and participation in a genocide, the proxy war in Ukraine, the incessant and increasingly dangerous provocations of China, the vassalization of Europe, the brutalizing sanctions against Iran, Venezuela, Syria, Cuba, and all such serious matters of policy. There is no need to think about any of this. There is, indeed, an unwritten code that the crises of our time, America’s leaders responsible for of all of them, are neither to be thought about nor mentioned.

It is brilliant, I would say, this mutilation of logic and reasoning. There is something for everyone in it.

For the Harris campaign the juvenile nonsense of joy and vibes is a diabolically effective blind. Behind it Harris’s people—and Kamala Harris is nothing more than the sum total of her advisers—can commit to continuing every one of the imperium’s foreign policies without the bother of public scrutiny. Just leave all that to us: This is the message the Harris people have as they flatly refuse publicly to take up any of the questions that should matter most to the imperium’s citizens.

And for those subscribing to the joy-and-vibes ethos, from Katrina vanden Heuvel on down, this is a twofer. They can persuade themselves they will stand against the established order by voting for the established order. Tell me you know anyone who has deceived himself or herself so cleverly as this.

And while arranging the wilted flowers in their hair, those populating the joy-and-vibes crowd can pretend to celebrate a state of elation while acquiescing to their candidate’s approval of mass murder. This is important to these people, for they must at all costs avoid facing their utter powerlessness, and so their subliminal depression, as they succumb once more to voting for an evil it is a stretch to consider the lesser of anything.

■

One question lingers as I glance again at the Kii Arens poster. What under the sun happened to the American left between its years at the barricades in the service of honorable causes and this, its time of weak-minded gutlessness? When did it pass from left to “left”? There is a book in the answer to this, the interior history of several generations, but I will keep this brief.

One of the remarkable features of the antiwar and anti-imperialist movements of the 1960s and 1970s, along with the principled feminists of those years, was the willingness of so many people—although not all by any means—to accept the necessity of sacrifice. Sacrifice and risk, I would say.

Such people understood: If you cannot stand for what you think is right and accept all the consequences attaching to being in the world authentically who you are, your thoughts and being are of no use. You understood the necessity of living beyond the fence posts, having concluded nothing of worth could get done within them if your intent was to work for genuine, radical change of the kind our civilization so obviously required then and requires now.

And so one gave up well-paid employment, or life in a good neighborhood, or holidays along the coast of Maine, or whatever else comprised one’s version of middle-class privilege. One accepted the need to respond to unexpected circumstances on the understanding that the world was other than what one was told it was. A certain precarity often accompanied these choices. Your car was a clunker. The heat pipes clanked.

Gradually over many years, the energy and commitment—the commitment to committing, let’s say—faded. I saw this in people younger than I as early as the mid–1970s. People wanted to think of themselves as “activist,” as “committed,” as standing for “change,” as—totemic word here—as “movement.” But in a short time the obligation to repudiate one’s bourgeois background for the sake of authenticity came to seem a mountain too high to climb. Careers came first. Careers, cars, houses, Williams–Sonoma kitchen gear. The thought took hold that one could get the worthy work done inside the fence posts and without giving up anything or taking any risks.

Deitrich Bonhoeffer, the celebrated German cleric who paid with his life for his resistance to the Reich, used to speak and write of cheap grace and costly grace. The former means, in secular terms, the pretense of an honorable life that involved no sacrifice. One’s neck need not ever be on the line. The latter is the opposite: To earn costly grace means to live and work honorably and paying whatever price one must to do so.

I am talking about the difference between the two as this came to be at the left-hand side of the garden over the past 50 or so years. It is all about cheap grace now.

A book I began reading last spring bears very well on this question. Anne Dufourmantelle, a greatly respected psychoanalyst who died tragically at 53 in 2017, published Éloge du risque (Payott & Rivage) in 2011; Fordham University Press brought it out as In Praise of Risk eight years later. After sitting on my shelf for several years, this has made its way among the most important books of my life.

We cannot live authentic lives unless we accept the constant presence of risk, Dufourmantelle argued over the course of 51 brief chapters (which do not have to be read in order). “Today, the principle of precaution has become to norm,” she writes in her opening pages. “Our days take place under the sign of risk. No dimension of ethical and political discourse escapes from it any longer.”

Dufourmantelle’s topic here is the life-depleting timidity so prevalent in Western culture. And her project is to write against this in favor of the risks inherent as we make all our choices—risks in relationships, risks in our victories and surrenders, risks in our public lives as well as our private, the risks altogether in how we live. “‘To risk one’s life’ is among the most beautiful expressions in our language,” she writes. Dufourmantelle does not say so, but she surely read her Sartre: In so many words, wonderful words, she is writing about what it means to be authentically free, to accept that we are responsible for the decisions every minute we are alive require us to make.

And the greatest of all risks, Dufourmantelle writes, is the first one we must take if we are to take all the others. This is the risk we assume when we overcome our fear of life itself and determine simply to live. It is, she says, “the risk of not dying.” And by not-dying she means a vital, dynamic embrace of the very next moment’s unknowability—or, turning the thought upside down, a refusal of the death-in-life to which most people succumb as they surrender to conformity, or to inaction, or to passivity, or to our paranoiac addiction to total certainty.

And so to my concluding point.

Kii Arens is merely a product of his moment, not to be singled out as anything more. His poster is a cultural text. It is testimony to the vulgarization of America’s public discourse, but it is nonetheless—or maybe for this reason—worthy of interpretation. Among other things, the iconography of his poster reminds us that the Harris-for-president campaign is in considerable measure a psychological phenomenon. It documents, in four words, a crisis of conciousness.

I read “Vote Joy 2024” not as a celebration of the Harris-for-president project but as an implicit admission of what is absent from it. It is a text recording, in the simplest terms, the regret of those who have refused the risk of not dying while envying those before them who took it.

This is an revised and expanded version of an essay that first appeared in Consortium News.

When the poster first dropped, some wag asked, “I’m not really into fashion these days, but is it appropriate to wear white to a genocide?"

As I connect these days to varying degrees with my old (65-75) “liberal” friends, Patrick’s descriptor, nostalgia, seems to sum their “reality” quite well. When an old college mate, who frequently plasters her posts with rainbows and trans triangles posted her exuberance at the news that the Cheneys and other Republicans had endorsed Harris, I replied, “I would think for any progressive, Cheney support would send chills down one's spine.” I also included a link to Tim Foley’s reading of the forthright Caitlin Johnstone’s post that very day stating, “…this election is now a showdown between the Trump Party against the Cheney Party, and no matter who wins, the empire wins.

Her one line response was, “We’ll have to disagree on politics.”

Really? While I’m sure we cannot agree on everything, I’m quite sure we could make common cause on a long list of things—if they could just admit that their Blue Team has long lost its way. I know Katrina vanden Heuvel and her late husband, Stephen Cohen, didn’t agree on everything, but to her buying into the giddy-joy campaign aligned as it is to all things Russiaphobic, surely must have him spinning in his grave (or his ashes in a whirlwind).