25 OCTOBER—The Scrum begins today to publish an extended essay on the Julian Assange case. We offer it as our contribution to the admirable worldwide effort to bear witness to the WikiLeaks founder’s courage as a publisher and, since 2019, his courage and extraordinary fortitude while imprisoned and subjected to the monumental corruptions of the British and American judicial systems. The essay was first published in the Summer 2020 number of Raritan, the quarterly journal, and will appear here in multiple parts. We have kept our post–Raritan edits to a minimum.

Whatever you have been led to believe: The Assange case is about YOUR future, YOUR life & YOUR right to know what YOUR government is doing with the power & taxes YOU give to them. I do NOT want to leave to my children a world where it has become a crime to tell the TRUTH.

—— Nils Melzer,

29 September 2021.

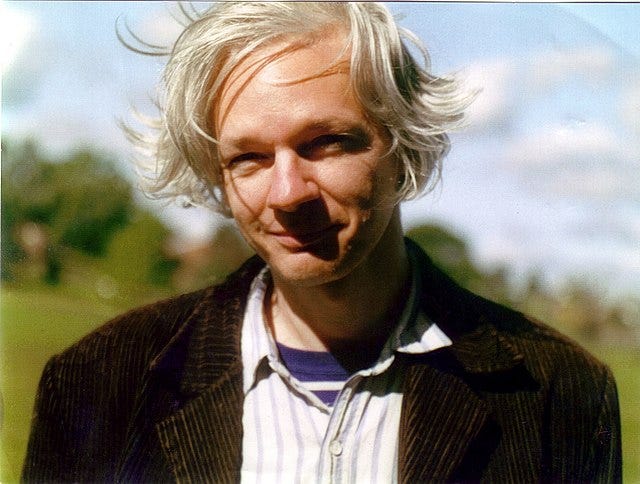

OF ALL THE IMAGES of Julian Assange made public over the years, three are indelibly haunting, even if, as we look at them, their import comes to us subliminally. These pictures date to the spring and autumn of 2019, when the WikiLeaks founder was arrested and imprisoned in London as a British court considered an American extradition request. In all three, he is photographed behind a pane of glass, a little as if he were a sea creature in an aquarium—near yet beyond our reach. In all three, he is confined in a security van about to take him away from crowds of press people, supporters, and, we have to assume, some stray passersby.

These are pictures of departures, then. When we look at them we find ourselves among those gathered at the scene and left behind. On the other side of the glass, with its strange reflections and refracted light, Assange is framed for us. He is remote within the frame, as figures in portrait paintings are remote. Even as he leaves us, Assange is already gone.

There is a Reuters photograph taken on 11 April 2019, the day Assange was arrested. Plainclothes police officers have carried him, corpse-like, down the steps of the Ecuadoran Embassy in Knightsbridge. His hair is long and brushed back severely, and he wears an unruly beard. From the police van’s window he offers a resolute stare. Handcuffed, he raises both forearms to manage a thumbs-up gesture. The checkered band of a London cop’s cap is visible behind him.

In an Associated Press photograph dated 1 May, a police van is taking Assange from a court appearance back to Belmarsh, a maximum-security prison in southeast London. His hair is short and his beard trimmed. His stare again conveys resolve. Assange holds up his left hand and curls his fingers into a fist. To his left in the picture plane, the glass reflects the distorted image of a brick apartment block. To his right, the flash of a camera illuminates an icy steel door just behind him.

The third image is a still from a video recorded after Assange had appeared in Westminster Magistrates’ Court on 21 October. He is in the window of a van that belongs to GEOAmey, a private company that provides “secure prisoner transportation and custody services,” as its website advises. Behind him is a steel door similar to the one in the second photograph, again illuminated by the flash of a camera. Assange is clean-shaven, gazing into the middle distance somewhere just above his head. The resolute stare is gone. Assange has no sign for us—we on the other side of the windowpane—no thumbs-up, no clenched fist. Some new kind of silence—a totalized, internalized silence—has been added to the silence imposed on Assange at the time of his arrest.

These images span six months. To place them side by side is to detect in outline the story of a very eventful half year in the life of Julian Assange. They are to me like shards of a broken bowl. Holding fragments of pottery in one’s hand, one imagines the unseen whole, the object that is no more. So it is with my prints of the Assange photographs. I spread them on my desk. I study them, one to the next to the next, then again the same. They seem to me tiny pieces of a shattered life, a life deprived, a life by turns taken away.

The story the images tell is Assange’s but also ours, in some measure the story of the way we now live in the Western democracies—or, better put, post-democracies. In this way the three pictures are mirrors, held up to us that we see ourselves as we are.

■ ■ ■

THE STORY of Julian Assange’s arrest in April 2019 begins in another April, this one nine years earlier. Assange’s exceptional endurance aside, there is nothing to admire in this story, much to hold in contempt. It is a story of false charges, cynical fabrications, unscrupulous prosecutors and judges, incessant breaches of law. There is physical abuse and psychological torture. Sweden, Britain, and latterly Ecuador have all conspired to deliver Assange to the United States for the offense, as is often noted, of breaching official walls of secrecy to expose multiple crimes, corruptions, and cover-ups. Assange is not charged with lying or disinformation or calumny or libel or anything else of this sort. The crime is exposure, shining the light of day where it must not shine.

I have wondered while writing this essay whether Julian Assange will ever again see the sky but from a walled and concertina-wired prison yard. At writing, his hour draws near. The British verdict on the Justice Department’s extradition request is due shortly. It is a foregone conclusion. There will almost certainly be an appeal. The prosecution’s case and the court procedure are multiply flawed, but again almost certainly, it appears a matter of time before Assange is put on a plane to face trial in a federal court in Virginia where such cases are typically heard and ruled upon. This verdict is another foregone conclusion. To describe these as show trials is perfectly responsible. And it is part of the argument here that we must be mindful of the history and connotations this freighted term bears.

To return to that earlier April: On 5 April 2010 WikiLeaks released “Collateral Murder,” the swiftly infamous video of a U.S. Army helicopter crew’s mid–2007 attack on unarmed civilians in Baghdad. Three months later came “Afghan War Diary,” seventy-five thousand documents that devastated official accounts of America’s post–2001 campaign in Afghanistan. These were two of the most damaging leaks in U.S. military history. For the first time in its brief life, WikiLeaks had penetrated deeply into the citadels of official secrecy. This was stunningly confirmed with the release of “Iraq War Logs” (nearly 392,000 Army field reports) in October 2010 and, a month later, the phased publication of “Cablegate,” a collection of State Department email messages that now comes to more than three million.

All of these releases derived from Assange’s work with Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning. They were a blunt challenge to the ever-advancing sequestration of power in our post-democracies and—let us say this now—to practices of mis– and disinformation that have long been routine in institutional Washington and the capitals of allied nations.

The 2010 publications stunned the Obama administration and the national-security apparatus invisibly but formidably behind it. There is much to suggest, on the basis of what is known, that Washington soon prevailed upon cooperative allies to encumber Assange with all manner of criminal charges, however far-fetched, trivial, or unrelated to the work of WikiLeaks these may be. Stratfor, a Texas company that provides intelligence services to a variety of defense contractors and federal government departments, began issuing directives of this kind within weeks of the “Cablegate” releases. “Pile on,” one of its advisories reads. “Move him from country to country to face various charges for the next 25 years.” It was WikiLeaks, ironically enough, that revealed these communications in a 2012 release called “The Global Intelligence Files.”

While teleologies cannot be countenanced, what Stratfor recommended—to official clients in Washington, we can cautiously assume—is a strikingly apt description of Assange’s fraught odyssey during the nine years prior to his 2019 arrest. Shortly after the release of “Afghan War Logs,” Swedish prosecutors alleged that Assange had raped two women while in Stockholm for a media conference. These allegations would haunt Assange for many years. We now know, thanks to an investigation by Nils Melzer, the U.N.’s special rapporteur for torture, that the Swedish case rested on corrupted police reports and fabricated evidence. Not even the two women with whom Assange had consensual relations supported prosecuting Assange on rape charges. Assange volunteered a statement to the Swedish police after prosecutors leaked falsified accusations to a Stockholm tabloid. He waited five weeks to be questioned, but Swedish authorities never brought him in. In autumn 2010 he decamped for London on his attorney’s advice and with Stockholm’s assent.

With the coordination of trapeze artists, Britain took over where Sweden had left off. British authorities arrested Assange two months after his arrival, citing a sudden Swedish request for his extradition. While released on bail, Assange took asylum at the Ecuadoran Embassy when Sweden declined to confirm that it would not reëxtradite him to the United States were he to return to Stockholm to cooperate with Swedish investigators, as Assange wished to do. In time, the Swedish case melted like ice cream in the sun. Prosecutors formally dropped their case on 19 November 2019. They had never charged Assange with any offense, and no allegation was ever substantiated, but they had done their work: By this time an obliging new government in Ecuador, acting at Washington’s behest, had canceled Assange’s asylum. He was arrested for violating the terms of his bail but was immediately faced with another extradition order—this one from the United States. Country to country, charge to charge: Sweden, Britain, and Ecuador acted, oddly enough, according to the design Stratfor had earlier proposed.

The Justice Department’s initial request for Assange’s extradition was unsealed the day he was carried out of the embassy. He was charged with a single count of conspiracy to compromise a government computer—this during his work with Manning—and faced a maximum sentence of five years. It seemed at the time an oddly modest case and an oddly modest penalty given the extreme animosity official Washington had nursed since Assange published the Manning documents in 2010. But more and much worse was shortly to come. On 23 May, six weeks after his arrest, a district court in Virginia unsealed indictments charging Assange with seventeen additional offenses—these filed under the 1917 Espionage Act. This was a precipitous escalation of the American case. Assange suddenly faced sentences of up to one hundred seventy-five years should he be extradited and found guilty of all eighteen charges now lodged against him.

■ ■ ■

“LIKE MANY YOUNG PEOPLE, I wanted to be on the cutting edge of civilization. Where were things going? I wanted to be on this edge. In fact, I wanted to get in front of this edge of the development of civilization. Because the old people were not already there.”

That is Julian Assange talking to Ai Weiwei in 2015. The noted Chinese artist had visited Assange three years into his asylum with the Ecuadorans. Their exchange is a contribution to In Defense of Julian Assange, a compendium of commentaries published a few months after Assange’s arrest at the embassy. “If you could learn fast you could get in front of where civilization was going,” Assange said the September day he and Ai conversed. “So I tried to do that, and I was pretty good at it.”

Assange became pretty good at it at a young age. He was hacking into the email queues of Pentagon generals while still a teenager in Australia. He understood very early that to be on the front edge of civilization meant penetrating the walls of secrecy behind which our most essential institutions—of government, statecraft, intelligence, defense—set the course of an ever more globalized civilization.

Assange’s thought was not his alone. By the time he was scoring his first hacking hits, it was plain that a “culture of secrecy”—Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s phrase—had grown like kudzu all around us. In Secrecy, Moynihan’s 1998 survey of the phenomenon, the late senator wrote of “secrecy centers” throughout the American government, of “the routinization of secrecy,” of “concealment as a modus vivendi.” Something called the Information Security Oversight Office—a secret in itself to most of us—each year totes up the number of secrets government bodies created during the previous twelve months. As Moynihan explained, in essence the ISSO counts the documents classified in a given year. These, too, seem to grow year to year like a Southern weed.

Assange’s original contributions to the questions of secrecy and concealment are four. One, he recognized, without inhibition and without allegiance to any orthodoxy, that our political culture’s infinitely elaborated structures of secrecy are, indeed, where civilization is going. At this point, it is commonly assumed among paying-attention people that a small proportion of what our government decides and does is visible to us. Two, Assange understood that these structures must be penetrated if authentic forms of democracy are to survive. Hence his thought as to where the edge of civilization lies. Three, Assange saw the vital, make-or-break responsibility of the press if the walls of secrecy are to be dismantled. Finally, he devised an extraordinarily innovative means to open up these structures—the national-security state and its numerous appendages—for the first time since this tentacled organism began to develop in the years after World War II.

Assange registered “WikiLeaks” as a domain name in Iceland on 4 October 2006. The site’s early publications were small bore—a Somali rebel’s assassination plots, the leaked emails of Sarah Palin, then a vice-presidential candidate—but its potential as a technology and a means to protect sources was immediately evident. In these early years, WikiLeaks was understood to promise something very new in journalism, a resource that could fundamentally alter relations between those practicing the craft and the powers they reported upon. Traditional media initially embraced WikiLeaks; governments cast a cold eye for the same reasons.

All of the major releases of 2010, WikiLeaks’ breakout year, derived from the Assange–Manning connection. Their work was made of what reporters and sources do in countless such interactions daily: Manning gave a journalist a story and evidence to support it; Assange cultivated his source and published the story. No serious appraisal of their relationship can otherwise describe what they did. But it is this relationship that the Justice Department deems a criminal conspiracy. This was the charge in the indictment unsealed the day of Assange’s arrest at the Ecuadoran Embassy.

It is not clear, even now, how many sets of documents Manning conveyed to WikiLeaks. In “Gitmo Files,” published in April 2011, WikiLeaks lifted the lid on the Army’s shockingly cavalier treatment of captives at Guantánamo Bay. On 24 June 2020, the Justice Department filed a superseding indictment against Assange, in which it alleges that Manning was also the source of these documents. In my view this is almost certainly so, but as WikiLeaks does not reveal its sources—Assange’s most essential principle—the origin of “Gitmo Files” has never been established. However this may be, it was not until The Guardian and other newspapers began publishing parts of Edward Snowden’s immense data trove, in the summer of 2013, that any breach of secrecy matched in magnitude the releases Manning had given Assange.

Manning and Assange paid, and paid swiftly, for their fruitful collaboration. Sweden and Britain soon had Assange careening through a hall of mirrors made of largely manufactured allegations. Manning was arrested a month after WikiLeaks released “Collateral Murder.” She then faced the first of numerous charges and was sentenced to thirty-five years’ imprisonment three years later.

Manning’s treatment while detained was not much different from what awaited Assange at Belmarsh: It was harsh and in breach of law. At the Quantico Marine Corps base, where Manning was initially held, she was deprived of sleep, confined to solitary for long periods in a windowless 6–by–12– foot cell, and at times stripped to her underwear. Juan Méndez, at this time the U.N.’s rapporteur for torture, described these and other conditions as “cruel, inhuman, and degrading.” It is unusual and by definition cruel that Manning was subsequently imprisoned at Fort Leavenworth, a men’s military prison, despite having announced just prior to her sentencing that she identified as a woman. By 2016, three years into her sentence, she had attempted suicide twice.

Three days before vacating the White House in January 2017, Barack Obama commuted all but four months of Chelsea Manning’s remaining sentence—roughly twenty-eight years of it. Her freedom was brief. In March 2019, she was rearrested on contempt charges after refusing to testify before a grand jury investigating Assange. Prosecutors knew Manning’s story well enough: She could not have spoken more plainly when she was first arrested. She had submitted to extensive questioning, confessed, and pleaded guilty at her earlier trial. They needed one thing from her this second time around: They needed her to support their conspiracy case against Assange. Manning had earlier testified that she acted alone when she hacked government computer systems. Now they wanted some indication, however scant, that Assange had directed her. An incautious phrase would do. Manning gave them nothing. “I will not participate in a secret process that I morally object to,” Manning stated, “particularly one that has historically been used to entrap and persecute activists for protected political speech.”

Manning returned to prison, this time to the women’s wing of a federal facility, on 8 March 2019. There she remained for a year, keeping the faith. On 11 March 2020 Manning made a third suicide attempt. A federal judge ordered her release the following day.

To be continued.

Courtesy of Raritan.

Every time you hear some lackey mewling about Muh Press Freedom when talking about a country that the Empire doesn't like, remember that Snowden is exiled, and Assange is de facto imprisoned on bogus charges.

No one seems to be able to think big picture here. We live in a crumbling society and the powers that be frankly revel in their corruption and evil. It would seem some larger strategy could be developed. As the old saying goes, in crisis there is opportunity. What ways can this situation be used? Personally I wrote in Assange/Manning in the 20 elections, since they are the only ones with any actual character in this whole shit show. They looked the Beast in the eyes and didn't blink. It doesn't get any better than that. Life is short and we all seem to be caught up in the details and miss the larger picture.

Obviously they want to make an example of Assange, not make him a martyr. Actually bringing him back for trial to the United States could prove to be a monumental error on their part, if the narrative can be reversed. How about finding ways to put him up in the pantheon of history's long list of martyrs, From Socrates, to Jesus, to MLK? How about posters of Assange next to Biden, asking who will history see as the real hero our age? How about "Free Assange" bumper stickers being printed up and handed out free on college campuses?

If twitter and facebook decide they need to cancel it, it will just go further to show how deep the rot is. There is the opportunity to throw this back in their faces. How can it be leveraged?